|

And will be again...

2021 An ethic of incommensurability...recognizes what is distinct,

what is sovereign for project(s) of decolonization in relation to human and civil rights based social justice projects. There are portions of these projects that simply cannot speak to one another, cannot be aligned or allied. We make these notations to highlight opportunities for what can only ever be strategic and contingent collaborations, and to indicate the reasons that lasting solidarities may be elusive, even undesirable... Opportunities for solidarity lie in what is incommensurable rather than what is common. – Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang, “Decolonization is not a Metaphor” Human beings in the true sense of the term can exist only where there is a world, and there can be a world in the true sense of the term only where the plurality of the human race is more than a simple multiplication of a single species. – Hannah Arendt, “The Promise of Politics” |

|

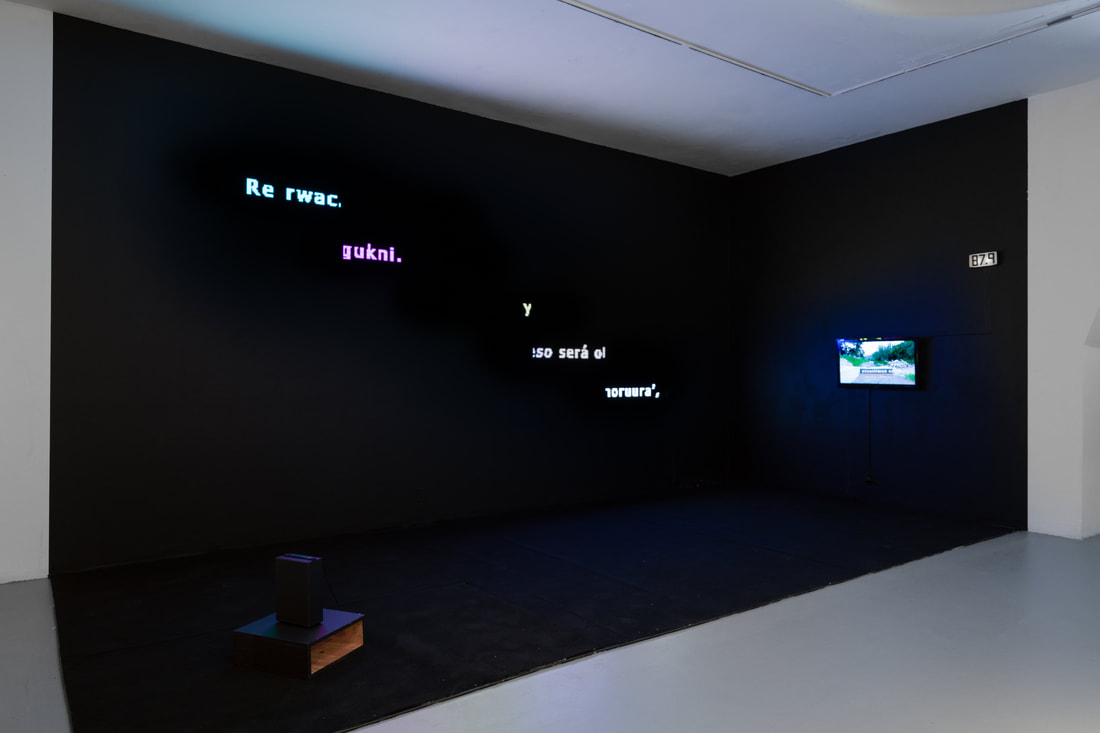

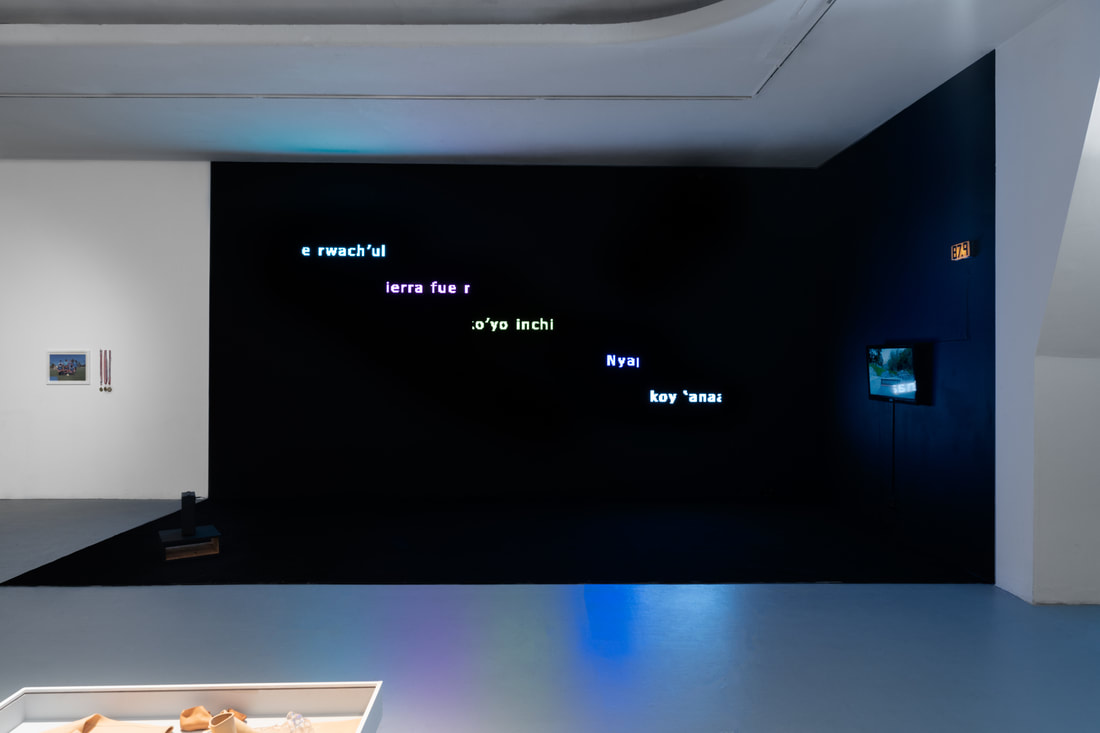

And will be again... was inspired by our interest in disentangling the relationships between borders, land and (de)colonization in the context of the greater Tijuana/San Diego region. In particular, the project sets out to interrogate the nature of borders as a colonial technologies, while also contending with what being in solidarity with a decolonial project – that seeks to return stolen land to indigenous peoples – would mean for those of us who are not indigenous to these lands.

As such, this project considers what – following Tuck and Yang – an aesth-et(h)ics of incommensurability might look like, what it might sound like. The title for the piece is taken from the last line of a Gloria Anzaldua poem in Borderlands / La Frontera: This land was Mexican once, We turn to this fragment of text and mobilize it as both a land acknowledgement and as an articulation of a decolonial project oriented around indigenous futurity. At the same time, we turn to this text as a gesture of critical assessment of how claims to land and indigeneity within some discourses emerging from Chicanismo can be(come) over-determined by the nation as model for structuring social, political and cultural relationships between subjects – in ways that can perpetuate the erasure of indigenous plurality and become stagnated in a metaphorical/symbolic pursuit of decolonization.

With this in mind, we worked with indigenous scholars and allies to translate the above phrase into 2 indigenous languages of the region stretching between Tijuana/San Diego and Los Angeles (Kumeyaay and Tongva respectively) as well as 3 languages (Mixteco, Zapoteco, Kaqchikel) that are spoken by indigenous communities who have migrated to this region from Southern Mexico and Guatemala and established sizable and significant communities who nonetheless continue to be invisibilized/marginalized. The process of translation becomes a way of issuing this call in a way that centers the voices of indigenous communities. As part of this, the text must confront linguistic limits – such as an absence of a notion of land as belonging to someone or the notion of national identity – and is forced to adapt and make certain concessions to several indigenous frameworks. The result is then translated back into Spanish/English as a glimpse of the incommensurability between colonial and indigenous frameworks represented in/by language. To carry this further, we became inspired by the fact that in many of the conversations we had with individuals helping us with the translation, we came across the fact that “border” as a term (especially in reference to a geo/political boundary) did not exist in many indigenous languages. Thus, to speak about a border – such as the one that exists between the U.S./Mexico – required undertaking the practice of circumlocution, meaning literally to speak around; a common practice when learning another language and you do not know/recall the exact word for an idea/concept/thing, so you describe this idea/concept/thing as best you can to communicate what you are intending to say.

This act of coming across something ineffable and speaking around it, appeared to us as an apt metaphor for the notion of incommensurability when seeking to communicate in ways that center plurality. This becomes the inspiration for a video poem that addresses the U.S./Mexico border across different local sites, scales and temporal orientations – thinking through the historical predecessors of the border in the mission system for example, and how the logic of division it embodies is imposed on the land in ways that also mark themselves on bodies in different ways. [1] To the end of thinking through the adjacent notion of plurality – especially as taken up by Arendt as the inherent human and political condition of being earthbound with other human and non-human animate and inanimate beings – we produced a soundscape for the installation which laces together several aural registers relating to land and borders, namely:

And finally, also included in the audio for the piece, are readings of the translated phrases in Tongva (Tina Calderon, Translation by Pam Munroe, and Gabrielino-Tongva Language Committee), Kumeyaay (Yolanda Meza, Nejí Kumeyaay), Mixteco (Miguel Angel Rivera Vivar, Mixteco de Xochapa, Guerrero), Zapoteco (Ignacio Santiago-Marcial Zapoteco de San Felipe Güilá, Oaxaca) and Kaqchikel (Translation by Edgar Esquit, recorded by Ixmukane Choy). These are also included below phonetically for reference. Meyaa 'ooxor xaroot Chichiinavro'am pomoo'ooxon, Taraaxatam pomoo'ooxon xaroot horuura', koy 'anaange xaa. Koy we'eeke xarooro. – Translation into Tongva by Pam Munro in consultation with the Gabrielino-Tongva Language Committee Nyapum nyaa shin tewa matt Jiku witt, Tipay witt rro, nyapum akwey wiitx. – Nejí Kumeyaay translation by Yolanda Meza Ñuu na koyo inchiyoa in kivii Na ndavi inchiyoa Ndana ndavi ndiko koa koa – Mixteco de Xochapa, Guerrero, translation by Miguel Angel Rivera Vivar Biú th chi. Guck yu’reé xten mexican Xtéen pá nu gukni Per sbireépa gack ni s’quí stuh – Zapoteco de San Felipe Güilá, Oaxaca translation by Ignacio Santiago-Marcial Re rwach’ulew re xok mexicano jun b’ey, jantape xok kichin ri qawinaq, k’a kichin na rije. Po xtok na kichin jun b’ey chik, ri chwaq ri kab’ij. – Kaqchikel translation by Edgar Esquit [1] Video-Poem [Excerpt] locations:

Otay Mesa, San Diego [Looking South] Southeast view of recently constructed border fencing in Otay Mesa [San Diego, CA], from across the street of commercial warehouses and storage facilities for goods manufactured across the border in Tijuana, Mexico. One possible derivation of the name Otay is the Kumeyaay "Tou-ti" meaning "big mountain." Mesa de Otay, Tijuana [Looking North] View from a hill in Otay [Tijuana] looking toward the Otay Mesa Port of Entry in the distance, overlooking a series of maquiladoras, exploitative multinational manufacturing factories, which saw a boom after the implementation of the 1994 North American Free Trade Agreement [NAFTA]. Cañon del Matadero [The Killing Canyon] / Smuggler's Gulch [Looking North] View of recently constructed border fencing from a hill in Tijuana overlooking el Cañon del Matadero, "the Killing Canyon", a.k,a, Smuggler's Gulch, a corridor which was used by smugglers to cross "contraband" and by migrants to cross extralegally. Smuggler's Gulch / Cañon del Matadero [The Killing Canyon] [Looking South] View from inside Smuggler's Gulch – an arm of the TIjuana River Estuary [San Diego, CA] – looking south into Tijuana, Mexico. The elevation difference causes eroded sediment and pollution from factories, as well as refuse from informal settlements to wash across the border into the estuary, leading to environmental crises. La Colonia Obrera [Tijuana, BC] Maquiladora factories on a hill by the Colonia Obrera, "the worker's colony", seen from outside the artists' family home. |